She was almost killed in the Boston Marathon attack. Two years later, five thousand miles away, a shark took his leg. If neither of those things had happened, they wouldn’t be married today. When our biggest pain brings us our greatest happiness, what do we call that?

The man and woman sitting on the worn-out couch are holding hands for a reason. They’ve been through things most of us haven’t, experiences so painful they’ve questioned whether life is worth living. You can see it in their faces, the way they sit, and the looks they share before speaking. They have a maturity that makes them seem older than they are: he with his messy reddish-brown hair and freckles, she with her olive skin, sharp cheekbones, and tattoos on her arms.

When disaster strikes, they say, you can choose to see it as random, as they once did. But randomness is hard to accept because it makes life feel chaotic and meaningless. On the other hand, seeing tragedy as fate, something that was meant to happen, can be just as difficult. It leaves you asking, “Why me? What did I do to deserve this?” That way of thinking brings guilt, anger, and shame.

But there’s a way out of this cycle. Finding that way out is the heart of their story, and it’s given them a deep understanding of life that stays with them. It’s also something they wouldn’t trade for anything. It’s why they’re here, sitting together on an old couch in a small rental far from home, still holding hands.

He remembers the moments before it happened. Water gently splashed against Colin Cook’s legs as he sat on his surfboard about a hundred yards from the shore of Leftovers Beach in Oahu. It was a little after 10:00 a.m., and he recalls the warm sun shining from the east. He had been out surfing for about two hours and felt exhausted but happy—the rush of joy that comes after a good workout. That October morning in 2015, he looked like an experienced surfer: broad shoulders, a lean build, and his V-shaped frame fit perfectly in his board shorts and wetsuit top.

He had moved to Oahu for moments like this. He left his childhood home in Rhode Island to enjoy the waves and beauty of the islands, along with the schools of fish and Hawaiian sea turtles he saw under his board that morning. At twenty-five, he could take life at a slower pace. Back east, everyone rushed to achieve things. To rebel against that, Colin first came to Oahu and rented a tiny walk-in closet to live in. The closet was next to a master bedroom in a two-story house owned by the man he worked for, who was also a surfer and entrepreneur. The closet was just four feet wide and fifteen feet long, and with the cot he had bought, there was hardly any space to move. But it was just steps away from a door that opened right onto the beach and ocean.

In 2015, he owned fifteen surfboards but only four shirts. He acted like a pro surfer, even though he wasn’t one. He convinced himself that he didn’t want to go pro because he thought competitions would ruin his passion for surfing. Instead, he worked on glassing, a slow and careful process of fiberglassing and sealing surfboards. His job was very different from his dad’s work as a sports-apparel executive and not the same life his sister had as an Ivy League graduate. Many times each month, Colin struggled with feelings of not having his father’s ambition or his sister’s intelligence. Those thoughts made him feel smaller than his five-foot-ten-inch frame. The only thing that calmed his mind, he found, was riding the next wave.

“I’m just going to catch a couple more waves before I head in to get ready for work,” he thought that morning in 2015.

Then it happened.

The force hit him like a truck. He was suddenly underwater, confused from the impact, then above water, gasping for air, and pulled under again, even more violently.

Colin opened his eyes and saw a tiger shark, twice his size, biting down on his left leg. He punched the shark on its nose—once, twice, again and again. Its skin felt rough against his fist. The shark thrashed and bumped into him, then pulled away. Colin made it back to the surface, panicked and struggling to breathe. He grabbed his surfboard and tried to paddle to shore, but when he looked behind him, he saw something shocking.

His left leg was no longer attached to his body. Just above the knee, it was gone, and blood was turning the blue water red.

Colin saw the shark’s fin coming toward him.

“Help!” he shouted. “Shark attack!”

Two nearby surfers noticed him and started swimming frantically to the shore.

I’m going to die out here, Colin thought.

The shark was already coming for him. He could see its eyes, its nose, and those terrifying teeth. Colin pushed and punched, fighting for his life, and somehow the shark turned away from him again.

But now the first three fingers of his left hand were bent at strange and painful angles.

Then, he went underwater again.

The leash, a thin cord that wrapped around Colin’s left foot and connected him to his surfboard, was now stuck in the shark’s teeth, while the other end was still tied to his ankle. The shark thrashed its head from side to side, trying to get rid of the leash and splashing water everywhere. Finally, the shark freed itself, and Colin quickly scrambled back onto his board. Blood was pouring from the open wound where his left leg used to be, creating a pool about twelve feet wide around him.

His vision began to blur and darken. Colin fought to stay awake.

In that struggle, time felt strange.

Suddenly, a large Polynesian man appeared on his own surfboard nearby. The man hit the shark with a paddle he held in both hands until it swam away.

The man threw his own surfboard leash to Colin, but Colin couldn’t grab it with his injured hand, and the blood dripping from the rope made it slippery.

Colin’s vision blurred again, and everything went dark.

Then he felt the water and the waves. The shark came back, its dorsal fin slicing through the water even faster than before, more furious than ever.

There was no way they would both survive.

“Tell my family I love them,” Colin gasped.

Meanwhile, Celeste, Kevin Corcoran, and their daughter, Sydney, were watching runners sprint toward the finish line on a chilly April afternoon in Boston in 2013. It was an overcast day, and the wind was biting. Seventeen-year-old Sydney was bundled up in a tank top, T-shirt, sweatshirt, and down jacket. Even though it was only 47 degrees, the Boston Marathon always felt like a citywide celebration. The Red Sox had played their annual morning game and won, and now the crowd from Fenway Park was in a festive mood as they headed to the marathon finish line about a mile away.

Celeste and Sydney moved through the crowd and between the metal fences along the sidewalk. They often got looks from people—Celeste had dark, styled hair and looked like she belonged to the beauty industry, where she had worked for fifteen years at a salon nearby. Sydney had her mother’s perfect skin and dark hair. They were waiting to celebrate with Celeste’s sister, Carmen, who was running her first marathon. Around 2:45 p.m., they pushed closer to the yellow finish line, looking down Boylston Street for Carmen.

In that moment of waiting, surrounded by the lively atmosphere, it was hard not to feel a little proud.

Just three years earlier, Sydney had been hit by a car while crossing a street near a relative’s beach house. She flipped up, hit the windshield, and fell hard on the pavement. Her older brother, Tyler, thought she was dead. Even after waking up in the hospital and being released, she struggled with headaches for a long time, only able to attend her high school in Lowell, Massachusetts, every other day. By the time she stood at the finish line that April day, Sydney had worked through three years of pain, anger, guilt, and depression. She finally felt at peace. They were waiting for Aunt Carmen, ready to celebrate not only her achievement but also Sydney’s recovery. Celeste believed the worst was behind them.

Then came a noise so loud it felt like it could burst her eardrums. Celeste felt as if she had been flipped through the air. She looked around and saw black smoke filling Boylston Street, shattered glass everywhere, and blood—blood everywhere. Celeste tried to sit up but couldn’t. She looked for Sydney but couldn’t find her. Kevin came into view and told her he was going to tie her legs with a belt. She looked down and saw that her legs were barely attached, with blood pumping out in rhythm with her heartbeat. Kevin tied the belt tight, then tighter, trying to stop the bleeding. Blood spilled onto his hands, and as he tightened the belt even more, the pain became so unbearable that Celeste thought she wanted to die.

Sydney was bleeding on Boylston Street.

She could feel something was wrong. Her right leg wouldn’t move the way she wanted it to. There was too much smoke to understand why, and she couldn’t see her parents. People were running around her, looking terrified, some covered in blood.

Where are Mom and Dad? she thought. Am I an orphan now?

She heard a ringing in her ears and smelled burning flesh. The smoke surrounded her, and she needed to get away from it. Sydney tried to focus and put pressure on her right foot to stand, but then she passed out.

When she came to, two men were over her. One was a Marine tying a tourniquet made of T-shirts around her leg. She gasped from the pain. The Marine told another man named Matt, who had gray hair and was wearing a plaid shirt, to press on her leg wound.

Matt did, and it felt worse: the pressure of his fingers squeezing her flesh. He pinched her femoral artery to stop the bleeding, and the men worked to tighten the tourniquet even more. It was excruciating. Matt and then another man named Zach, wearing a gray New Balance T-shirt, were trying to take off her shoe because there was blood coming from her left foot. Sydney’s thoughts went beyond the pain. Are there more bombs? Will I survive this?

Her vision blurred, then went dark again.

Matt pressed his forehead against hers. “Just squeeze my hand, keep talking,” he said.

She nodded, but time felt strange. When she came to again, she was in a medical tent set up for marathon runners and now for bombing survivors. It was a chaotic scene where people were cutting off her pants with scissors and saying things she could hear, like “Her eyes are white! Lips are purple! Get her in an ambulance!” She wanted to tell them how scared she was, but she was too exhausted to speak. She felt so cold and wished her family were there. Why weren’t they with her?

I am an orphan, she thought.

Sydney found herself in an ambulance, with a tourniquet—was it the same one from the street?—tied even tighter. Pain pulsed through her leg with every bump and turn, while someone moved in and out of her blurry vision. Everything felt white and fuzzy.

I know I’m going, she thought, and I had an okay run.

A calm feeling spread through her. She could still hear the rumble of the tires on Boston’s streets and the urgent movements of the people around her, but now there was a warmth from them that matched the warmth growing inside her.

This is one of the most peaceful moments I have ever known, she thought.

The next day, Colin Cook was in a hospital bed at Queen’s Medical Center in Honolulu. He looked around the white room and remembered bits and pieces of what had happened.

He recalled the large Polynesian surfer, who had been with him, and how he thought he was going to die. He remembered vague words about his injuries—“two inches above the left knee”—and the need to fix the fingers of his left hand that were hurt by the shark. Now, on this second day, he was coming off strong medication, feeling pain from the surgeries but also a sense of calm. My God, I am alive, he thought.

His dad, Glenn, and older sister, Cassie, were the first to arrive. When Glenn heard the news about the shark attack and Colin’s emergency surgery, he dropped to his knees to pray, but instead, a scream escaped him: “You are not going to take him! You’re going to take me!” Now, seeing Colin, hurt but alive, filled Glenn with pride, and he blinked back tears.

A doctor knocked and entered the room to check Colin’s vitals. Colin took the chance to look at his phone.

“What are you looking at, Col?” Glenn asked.

“Watching a live feed of the North Shore’s waves,” Colin replied.

Everyone laughed.

But then the doctor said Colin would be lucky to walk again, and the laughter stopped.

Colin’s mother, Mary Beth, arrived next. She and Colin had always been close. Before his parents divorced, Glenn traveled a lot for work, so Mary Beth found ways to connect with Colin. They went dirt biking, and she even taught him carpentry, knowing he struggled to sit through school. His ADHD made school hard for him, and it hurt his confidence. Colin became shy and anxious over time. He had a few friends but no large social circle and no long-term girlfriend. Mary Beth was his confidante and support, helping him with homework, answering questions, and giving advice. She even watched him surf, even in Rhode Island’s cold winters, while he battled the waves in a bodysuit and she stayed warm in her car.

For Colin, the only thing that felt right was surfing. It quieted the negative thoughts he had about himself, telling him he wasn’t good enough. He never felt he measured up to his successful dad or his sister. He had the skills to be a pro surfer—others said so—but he could never convince himself of it. The same went for dating; despite his good looks and kind nature, conversations with girls often felt awkward. He overthought everything he said, leaving him barely able to speak before they walked away.

Only Mary Beth and surfing could help Colin when he was feeling his lowest. In the hospital room, he looked at his mom and asked, “When do you think I’ll be back on a board?”

What can I say? she thought. How do I tell him he might never surf again?

But seeing how weak he was, with his pale skin from blood loss, she didn’t want to crush his spirit.

“One day,” she said softly. “You’ll be back on your board one day.”

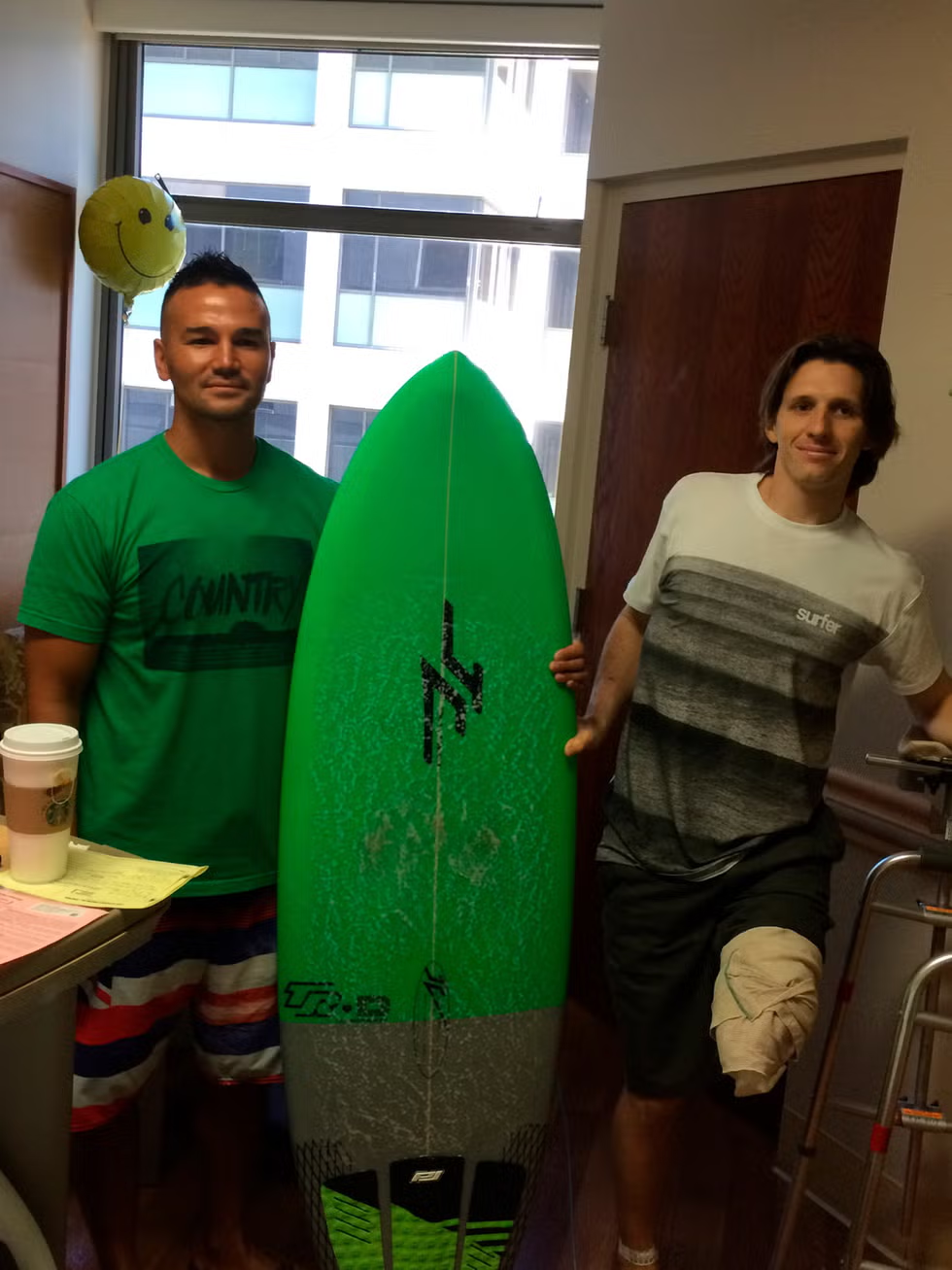

Colin ate the meals his family brought in, and soon friends came to visit, followed by surfers he didn’t know—people who had seen the news about the attack. One day, a large, muscular man knocked on his door. He introduced himself as Keoni Bowthorpe, a thirty-three-year-old with a strong jaw and a family history on the islands.

Keoni explained how he had fought the shark, hitting it on the nose more times than Colin remembered. They were far out, about 150 yards from shore. When Colin gasped, “Tell my family I love them,” Keoni realized Colin was in serious danger. Out of desperation, he dropped his paddle—the only thing he had to protect them—and pulled Colin onto his back, lying flat on the surfboard as he swam to safety. The shark followed closely, bumping against them as Keoni’s muscles burned from the effort, still so far from shore.

Keoni talked to Colin in the hospital, sharing his belief that God was present in the ocean. He had a wife and three young kids and had been offered a job on the mainland that would have provided for his family. But something told him to stay on the islands and focus on becoming a better surfer and swimmer.

“God prepared me to save your life,” Keoni told Colin. “And God has been preparing to save your life, too.”

Colin wanted to believe him and hoped he could get back to his old life, but once Keoni left, he found himself searching online for surfers who had lost a leg above the knee and returned to surfing. He found a few, but none of them could surf like they used to with a prosthetic.

There’s no way I’m good enough, he thought.

Under the bright hospital lights, listening to the machines beeping around him, Colin cried. A new thought crossed his mind: What if the attack wasn’t the worst thing that happened to him?

Kevin Corcoran had a different kind of fear as he rushed his wife, Celeste, into the emergency room at Boston Medical Center. The doctors said they would have to amputate her leg. He knew Celeste’s life would be forever changed, but that wasn’t his worst fear.

He couldn’t shake the thought of why he hadn’t found their daughter, Sydney, at the finish line. He had been just a few feet behind them when the bomb went off, and he had seen it knock Sydney down.

What if she was gone? Was that why he couldn’t find her in the chaos while he helped Celeste? She kept asking where Sydney was, and he didn’t have the heart to tell her what he feared.

Instead, he reassured her, “Sydney’s okay.”

Now, with Celeste in surgery at the hospital, Kevin broke down in tears.

He and Sydney’s older brother, Tyler, asked about Sydney over and over. After two long hours, they finally got news: Sydney was alive and at the hospital. The doctors had to take veins from her left leg to create a new artery in her right leg, but there were complications with blood pooling at the site. They had to make another incision in her right calf to relieve the pressure. But eventually, Sydney woke up and started to recover, and she was placed in the same room as her mom, Celeste.

Celeste was still waking up from her surgery when she was taken to the recovery room. There, she saw her daughter, Sydney, looking pale and with messy hair. Celeste looked down at her own legs and the part that was missing, then reached out to hold Sydney’s hand.

For hours, they held each other’s hands, comforting one another.

Meanwhile, Colin was back in his childhood home in Rhode Island, trying to put on his prosthetic leg. He struggled to get it on and grimaced with discomfort. The house was on Seapowet Avenue, near a saltwater estuary that led to the Atlantic Ocean. His dad lived there, and while Colin was recovering, his mom, Mary Beth, rented a nearby place to help him.

Colin’s new leg was heavy and didn’t fit well. When he tried to walk in the living room, he stumbled and fell to the floor. The nerve endings in his residual limb hurt, and his skin needed time to toughen up so he could feel less pain. No matter how hard he tried, walking on the prosthetic felt like wearing an awful ski boot that was too stiff. The leg didn’t work like a real knee, which made surfing feel like an impossible dream.

Doctors said it would take time to get used to the prosthetic, but as time went on, things didn’t get better. The pain in his leg made it hard for him to stand, and he could only walk a few steps before he had to stop. He couldn’t shake the thought that there was something worse than the attack itself.

In February 2016, Colin and his mom flew to Florida. When they arrived in Orlando, he used crutches to get around, and he felt a sense of dread as they approached their destination: the large Prosthetic & Orthotic Associates clinic.

The Prosthetic & Orthotic Associates (POA) had a dark glass entrance and a rehab facility that stretched for a city block. It was designed to stand out from other prosthetic centers. Stan Patterson, the founder, was a big guy with a buzz cut. He greeted Colin and his mom, Mary Beth, with a firm handshake. Patterson had many patents and an on-site lab where they made custom prosthetics based on silicone molds of a person’s limb.

“We’ll have you walking in a week,” Patterson promised.

Colin didn’t believe it. He smiled slightly but thought, How could Stan from Orlando help him when the experts back home hadn’t?

Patterson noticed Colin’s doubt and took them to the large rehab room. There, they saw many amputees trying out new prosthetic legs. Patterson introduced them to a middle-aged woman with diamond bracelets and pearls around her ankles—her prosthetics were fancy.

Her name was Celeste Corcoran, and she was a patient at POA. Her strong Massachusetts accent made Colin and Mary Beth feel comfortable.

Colin had learned that amputees often joke about how they lost their legs. When Celeste asked him what happened, he replied, “Shark attack,” in a serious tone. It took her a moment, but then she laughed and started calling him Shark Boy.

Celeste shared her story about the bombing and how she had been in a shared hospital room with her daughter, Sydney. She talked about how they held hands but also about her sadness when she looked at her own body. Her legs were bruised, and she felt pain in the parts that were gone, which is called phantom limb syndrome. At night, when she thought Sydney was asleep, Celeste would cry.

One day at POA, she showed Colin and Mary Beth a photo of Sydney. Mary Beth remembered seeing them in an interview on the Today show after the bombing. Sydney’s voice was hoarse because she had been on a breathing machine, but they both refused to be seen as victims. “If you have the spirit and you know that you want to do it—I can absolutely achieve it,” Celeste had said.

Celeste shared with Mary Beth and Colin how POA gave her not just new legs but also a new outlook on life. She said that Sydney had become just as strong and mature. After being released from the hospital, Sydney’s classmates at Lowell High voted her prom queen. Reporters camped outside like paparazzi, waiting to catch a glimpse of her. Sydney chose a strapless cream dress and walked in on crutches, proudly wearing her crown for the cameras.

As Celeste looked through recent photos of Sydney, she noticed that even without the crown, Sydney had a regal beauty.

At the end of Colin’s week at POA, Patterson helped him into a new custom prosthetic. Because of their special method, this prosthetic fit snugly around Colin’s knee and was comfortable, unlike the others he had tried. With the above-the-knee amputation, Patterson showed Colin how to swing his hip to walk. “Hip swing, step forward,” he instructed, walking beside Colin.

Then Patterson stepped back. Colin took his first steps—slow and awkward but he was moving. He couldn’t believe it; he was walking again! He smiled and let out a happy laugh, just like he used to when surfing.

Seeing this, Mary Beth cried tears of joy and looked at Celeste, who was also in tears.

Celeste and Mary Beth became close friends and started planning to get Colin and Sydney together. Colin, however, was too focused on his own success at POA. He was determined to surf again.

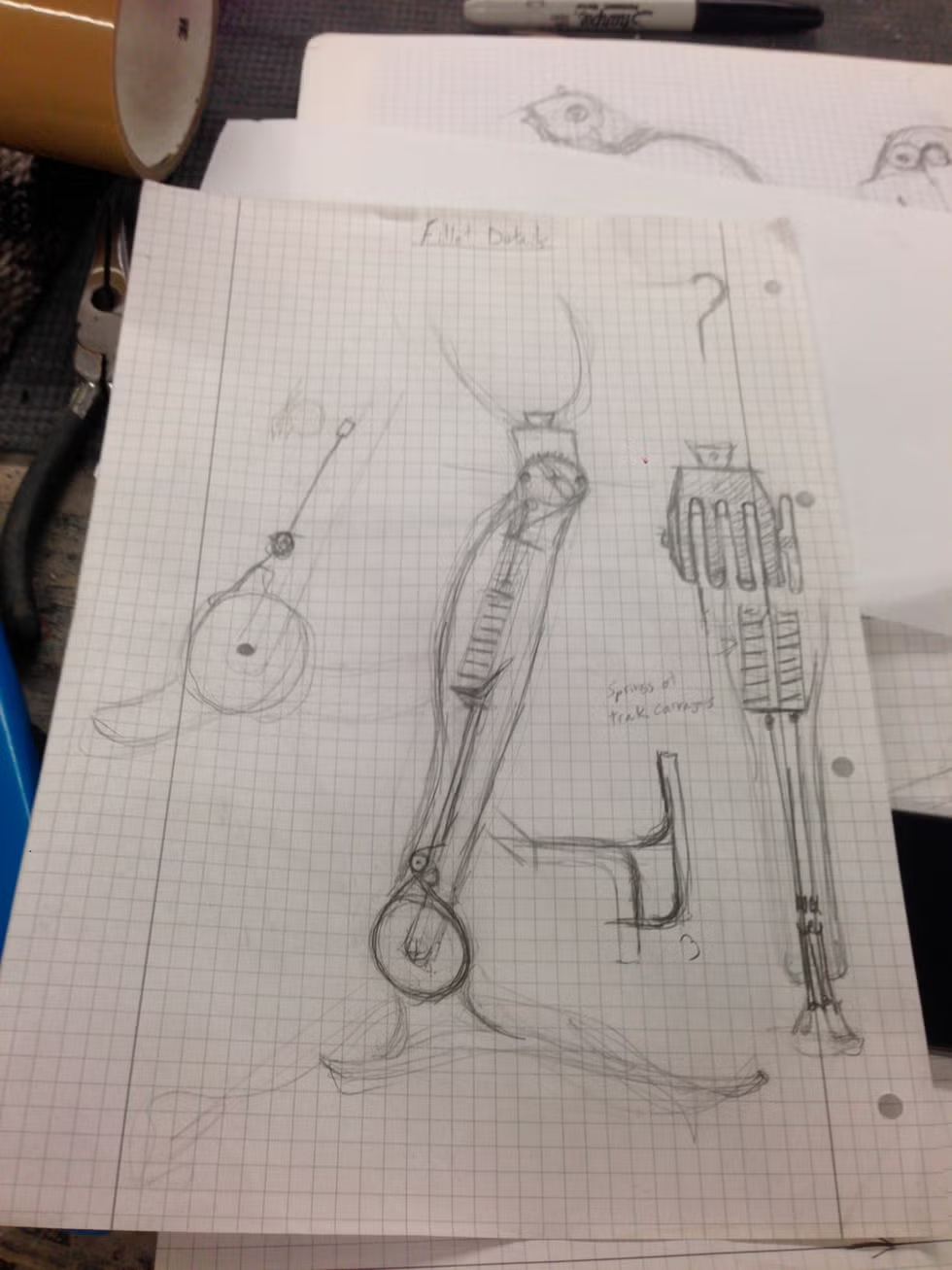

The demand for surfing prosthetics was low, and the existing ones were all designed for people who had lost a leg below the knee. There were no above-the-knee options because they were difficult to make. Creating a prosthetic that mimicked a knee joint and fit a surfer’s unique foot on the board was a big challenge.

To solve this problem, Colin began sketching his ideas for a surfing leg. He envisioned something less like a stiff wooden leg and more like the curved blades used by Paralympic sprinters. This design would allow him to be active on the board, helping him squat and pivot. He imagined a curved-blade prosthetic that could connect to a ball-socket knee and fit snugly to his limb, like Patterson’s design.

Colin reached out to two childhood friends, Brendan and Max, who were engineers in Rhode Island. He asked them about the carbon fiber they used in their projects and whether it could help him create a new surfing leg.

The first version they made worked well for standing and walking, but the blade was too long for Colin to squat on his board. They tried again with a shorter blade, but the knee joint wasn’t strong enough. When Colin made quick movements, the knee would buckle and fall behind him. They wondered how any manufactured knee could handle the force of water against it.

As they continued to work on new designs, they noticed another issue: the carbon-fiber tip of the new leg didn’t provide enough balance when he pivoted sideways. They attempted to put the blade inside a sneakered foot they made, but that didn’t work either; the sneaker would slip off on wet surfaces.

They thought about creating a foamed composite foot—something that would let the carbon-fiber blade attach to it. This foot would act like a sponge in the waves, absorbing water without sliding off the board.

Within days, the three friends began making foamed feet using the same materials that high-end sailboats are made from. Soon, Colin’s house was filled with these foamed composite feet. He wanted a foot that was sticky enough to grip a wet surface but not so sticky that it felt glued down. None of the designs worked perfectly, so they ended up making ten feet instead of just five, and they piled up all over the house. Colin’s dad, Glenn, watched their intense work and smiled, thinking that this was just who Colin was. “OCD,” he joked.

Colin kept sketching small changes and writing down his ideas, eagerly waiting for 5:00 p.m. to start working on the next improvements with his friends. His mom kept reminding him about a charity event in North Chelmsford, Massachusetts, but he hardly paid attention. He was so focused on his designs that he only realized they had to leave for the event when his dad told him.

The night was a fundraiser for 50 Legs, a nonprofit that helps cover the cost of prosthetics. Celeste Corcoran, who received her prosthetics from 50 Legs after the bombing, would be there as an honored guest, and Colin’s parents mentioned that her daughter would be there too.

Colin put on an old flannel shirt and rolled up his pants on the prosthetic side. He just wanted to get through the event and return to his designs. Glenn drove him there. Colin’s mom was back in Georgia, but she had given Glenn strict instructions to make sure Colin and Sydney met.

As they entered the event, Colin felt nervous. There were almost two hundred people, with food, drinks, and a band playing. He thought, “Oh man, this is going to be awkward.” In a loud place like this, he could easily get self-conscious and not know what to say.

Then he saw Celeste. She was fast-talking and full of energy as she shook Colin’s hand, introduced herself to Glenn, and quickly turned the attention to her daughter, Sydney, whom she hoped would be the highlight of the night.

Sydney wore a black dress that ended above her knees. She was twenty-one now, three years after the marathon bombing, and her dress showed the surgical scars on her toned right leg. The tattoos on her arms and back told the story of how she learned to take control of her life. You could see in her eyes that she had told her mother she was tired of the immature “boys.” She wanted to meet a man who had been through tough times and grown more confident from those experiences, just like she had.

When she looked at Colin, he managed to say, “Nice to meet you.”

The moment felt long and awkward. Colin was definitely attracted to Sydney, but he was also nervous about her beauty and maturity. His constant worry that he wouldn’t say the right thing made him say very little. Sydney didn’t know how to continue the conversation.

So she walked away.

Later, while Sydney and her mom, Celeste, chatted with others, Colin stood across the room, stealing glances at Sydney but too shy to approach her. Glenn, Colin’s dad, heard his ex-wife’s voice in his head, telling him to help their son. He decided to go talk to Sydney.

“Hey,” Glenn said. “Just so you know, this is how Colin usually is. If you want to connect, you should get his number.”

Sydney nodded. She had heard from her mother about Colin’s journey at POA and how he learned to walk again. She thought maybe he would understand her, especially since she had gotten her whole family involved in group therapy. She wanted to know if he would get her tattoo of a lion across her back and the words “choose to live” on her wrist.

With that in mind, she crossed the almost empty hall to Colin.

“Hey,” she said when she reached him. “If I gave you my number, would you text me?”

On the night of their first date, Sydney was late because of awful traffic, so they had to rush through dinner. Colin was too nervous to eat much, worried he’d say something stupid, and kept excusing himself to the bathroom, thinking he might be sick.

They hardly talked. Then they went to see a movie where they couldn’t talk at all. The movie was The Huntsman: Winter’s War, a sequel to Snow White and the Huntsman, and it was just as bad as you’d expect. After the movie, Colin walked Sydney back to her Volvo SUV but didn’t try to kiss her because he didn’t feel like he deserved to. He watched her drive away, then got back on the highway to Rhode Island. Just then, his phone rang.

She asked Colin if he was still in the parking lot. When he said no, she joked that it was too bad because if he were, she would drive back and give him a kiss.

They planned a second date, which led to more dates. Colin began to feel uneasy, worried that he might mess up this good thing. About a month into their relationship, he drove to the Corcorans’ house north of Boston, near the New Hampshire border. Sydney and her parents had moved there after the bombing. The house was large and had been modified for Celeste’s wheelchair, which she used when her leg pain became too much.

Colin tried to keep things light with Celeste and Kevin. Celeste still liked to call him Shark Boy, but one moment, just him and Sydney in the living room, he turned to her and asked, “What do you even see in me?”

Sydney looked surprised and unsure if he was serious. Colin continued, “Isn’t it weird that I’m an amputee? I mean, how many amputees do you need in your life?”

Sydney realized he was serious and replied, “Look out that window.”

He saw their green front yard, an acre back from the road, on a bright summer day.

“Look for all the fucks I give,” Sydney said.

Colin laughed, and she did too. She told him that his experience didn’t burden her; she liked it. She painted the fake toenails of her mom’s prosthetics all the time. She understood his life because she had been close to death too. Now, she was there with him.

In the following days, Colin called and texted Sydney, feeling more playful than he had with any other girl. Meanwhile, he and his friends kept working on his surfing leg and foamed foot. One day, he told his dad he was heading out, too excited and nervous to say where he was going.

He went to the beach to test his surfing leg for the first time. Out in Rhode Island’s gentle waves, the knee buckled beneath him. The joint couldn’t hold his weight against the rushing water, and the foamed foot kept slipping off the board. The first attempt didn’t go well. But as he swam back, something changed inside him. He didn’t feel the despair he used to. Was it because of Sydney’s influence? He wasn’t sure, but he felt motivated to keep trying. He and his friends adjusted the knee joint, hoping to make it more stable.

Days later, Colin returned to the beach. The many months of fitting and adjusting his surfing leg had been frustrating and painful at times. His left limb wasn’t fully used to the prosthetic yet, so he had to take breaks between trying it on and testing it again. On this day, he felt close to not just creating a unique prosthetic, but also to discovering a new version of himself.

At the beach, he carefully attached his surfing leg. He lifted his board and swam out. On the first big wave, he pushed up—

—and the foot stayed on the board. He maneuvered and pivoted, water crashing around him, and—

The knee held strong. The foamed foot absorbed the water.

He pivoted again and realized,

MY GOD, I’M SURFING!

When he got back to land, Sydney was the first person he wanted to tell.

The more he surfed, the better he felt, until he reached a decision that surprised even him. He wanted to win competitions with his new leg. He wanted to turn pro. It felt crazy: Colin Cook, competitive surfer. But that’s what he wanted now, maybe for the first time. Perhaps he had always been too afraid to admit that desire for fear of failing.

To become a professional surfer, Colin realized he needed to move somewhere with better waves than the small ones off Rhode Island or Massachusetts. Although Hawaii was a popular choice, Sydney remembered how Colin had lived in a cramped walk-in closet there. Instead, they decided to move to Southern California, where Colin had family and Sydney could find work in the surfing industry—most pro surfers needed a day job. Colin got a job designing surfboards in Oceanside, a beach town south of Los Angeles. They rented a place near the water in Laguna Niguel. But slowly, their lives began to unravel.

Sydney missed her family. Her mom was her inspiration, and her brother was her best friend. They had all lived in New England for generations, and although Sydney had thought she wanted to live somewhere else, she didn’t feel as confident as everyone assumed she was.

She carried the memories of the bombing and the days, months, and even years of reliving it. Whenever she felt uneasy in new situations, she remembered the words of writer Viet Thanh Nguyen: “All wars are fought twice: The first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.” Sydney understood that the war didn’t end with the bombing; it continued in her mind. In California, she began to question if she had ever been truly confident.

The fear started right after the bombing. Although she had put on a brave face for interviews with shows like Today and The Boston Globe, deep down, she was a scared young woman who had nearly died in a car accident and had then found herself at the finish line of the Boston Marathon. Recovering from her second near-death experience, she thought, “The universe doesn’t want me here.” It felt like death was stalking her. When she shared a hospital room with her mom, she couldn’t help but think about what the bomb had taken from Celeste. She often wondered what she had done to deserve this suffering for her mother.

These thoughts plagued her, leading to dark feelings. The part of Sydney that still wanted to live held on tightly to one thing she could control: her food intake.

She limited what she ate at meals or sometimes skipped meals altogether and worked out excessively. The physical therapists who helped her in Boston and the news crews covering her story praised her commitment to rehabilitation, as she was already walking again despite the surgeries on her legs. They admired her resilience.

But Sydney thought it was all nonsense. As her thoughts became darker in the weeks and months following the bombing, her workouts intensified, and her struggle with anorexia worsened. Then the nightmares began. In one vivid dream, she crawled through a muddy obstacle course, dodging barbed wire, then jumped up and ran as she saw and heard explosions and gunfire. The Boston Marathon bombers were chasing her, explosives in hand and hatred in their eyes.

She would wake up screaming, soaked in sweat. She tried therapy for her PTSD and anorexia, which helped somewhat, but the dark thoughts and nightmares returned. She struggled to focus at Merrimack College and eventually dropped out.

Then she met Colin Cook, who had a different outlook. After his attack, he said he was no longer afraid of sharks, which amazed her. About six months into their relationship, he even convinced her to travel to Hawaii with him, to the waters where he had lost his leg, and swim with sharks. Sydney was nervous, but Colin was calm. With local shark experts guiding them, Colin swam with Galapagos and reef sharks, even letting them swim around him. Back on land, he shrugged it off, saying, “The ocean is their home.” His bravery inspired Sydney.

Colin made her feel strong, especially when he struggled with his own insecurities about becoming a surfer. From the beginning, Sydney had a knack for uplifting him, like when she joked, “Look for all the fucks I give,” which had made him laugh.

As their relationship grew, Sydney felt useful and loved, which deepened her love for him. She agreed to create a new life in Laguna Niguel, but the unease and dread of new situations returned. She realized she had only been able to support Colin because of the help she had received from her own family back in Massachusetts. In California, she felt lost and malnourished. Her longing for home wasn’t just homesickness; it felt like a loss of identity. Calling home five times a day only made it worse. Even though their neighbors were friendlier than people back East and their cozy apartment had beautiful sunsets, Sydney felt unanchored in California, leading a quiet life filled with sadness.

Meanwhile, Colin thrived in California. He had his job, big waves, and a growing group of friends to surf with. With Sydney’s support, he discovered adaptive surfing competitions and was ready to show off his new skills.

But Sydney’s support no longer felt fulfilling. She cried daily—every night, most mornings, and much of the afternoon.

Colin didn’t know what to do. “Can you, like, try to be happy?” he asked her.

“I’m trying. I’m really trying,” she replied.

They never settled on a clear plan for their future. Instead, they focused on their present, which was loving and improving day by day but still haunted by the past. By 2019, Colin had competed in many adaptive surfing competitions and had won the U.S. Nationals twice, but he struggled at the World Championship in California. During that competition, it felt like he was back in the big hall in North Chelmsford, Massachusetts, meeting Sydney for the first time: the stage felt too big, filled with too many talented surfers, and he felt overwhelming self-doubt.

Despite their past struggles and how they helped each other stay focused on the present, their love deepened. As Colin prepared for the 2020 Paralympic championships—starting with a statewide competition, then nationals, and possibly the Worlds—Sydney reminded him that he wanted to be more than just a victim of his attack. Winning the Worlds would show that he had overcome that day and moved forward. “You’ll win when you can believe it,” she told him.

Colin expressed his fears, saying, “There’s no way I’m good enough for that.”

He took on the regional and national competitions again, and in mid-March 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic shut everything down, Colin stepped onto the beach for the International Surfing Association’s World Para Surfing Championships in La Jolla, north of San Diego.

A crowded beach filled with 131 surfers from 22 countries greeted him. On the opening day of the five-day competition, Colin paced the beach.

Although he couldn’t silence his inner critic demanding perfection, when he got into the waters of La Jolla for his first heat, that voice quieted enough for him to focus on winning and moving on to the next round.

For four days, Colin kept winning. He performed so well in each heat that he became the favorite going into the finals.

On the morning of the final day, he couldn’t shake the feeling that he would mess it up because that’s what he always did at Worlds.

Sydney heard his anxious self-talk in their hotel room and on the beach. It was the same doubt he had expressed before previous competitions and throughout their relationship: “I’m not sure I can do this. I’m not sure I want to. Why am I even here?”

She approached him, looked deeply into his eyes, and interrupted his pacing.

“You are a great surfer,” she said. “Do this for the love of surfing.”

Soon, the three finalists—Colin, Eric Dargent from France, and Naomichi Katsukura from Japan—hit the water together.

To his loved ones—Mary Beth and Sydney holding hands on the beach, and his dad watching the finals from Rhode Island—Colin seemed just like the same old Colin. He patiently waited for the right wave, letting the other competitors go first. He was pushing himself to be perfect.

But out on the water, Colin was in a different place. Everything around him faded away—the other surfers, the stress. It was just him, the waves, and Sydney’s words echoing in his mind: “Do this for the love of surfing.”

He understood what she really meant.

Then the perfect wave came, and he rode it. He caught another perfect wave, too.

When he got back to shore, the judges confirmed it: he had done well.

In April 2023, they married in a simple ceremony on the beach of Oahu’s North Shore. Sydney wore a lace wedding gown, and Colin dressed in shorts and a Hawaiian shirt. They chose that date because April was when they first met, and 2023 marked ten years since the Boston Marathon bombing, a day that ultimately brought them together. “Getting married ten years later claims the date for ourselves,” Sydney said.

Now they live in a small rental on the North Shore of Oahu. When they talk about their past experiences, they often hold hands on their cozy couch. Moving further away from Lowell was a risk, but Sydney found what Colin has always loved about the island. During their hikes to the top of lush mountains, admiring the Pacific Ocean, or during morning coffee walks in sandals, Sydney enjoys the slow pace of island life. They have learned to appreciate the moment, as it’s all they truly have. She’s feeling better now; the dread and loss of her former self are behind her. She’s also taken her own advice, ignoring the fears that arise when going after what she wants. Her journal entries have evolved into writing she hopes to publish. She left her corporate job—something she never liked—to start making candles that she ships to an ever-growing list of clients on the mainland.

Surfing was included in the summer Olympics, and adaptive surfers are set to compete in future Paralympics. Colin is excited about the possibility of becoming Colin Cook, Olympian. Even he laughs at how big his dreams have become.

Sydney continues to help him shape those dreams. She has to. Some mornings, Colin wakes up eager to surf but feels afraid that a shark might bite him. The fear has resurfaced since they moved to Hawaii. The PTSD from his past has come back after six years and can sometimes stop him from surfing altogether. The only thing that helps him is Sydney. On his worst days, when his anxiety feels like a heavy weight on his chest, she guides him to the beach. She watches while he puts on his surfing leg, often saying nothing.

After taking a deep breath and with a nod from her, he makes his way into the water. “Just knowing she’s back there…” he later says, struggling to express how much her presence means to him.

By the time the first wave hits, he feels fine. He becomes New Colin.

He surfs and improves.

When he comes back to shore, Sydney is still there. The two of them hold hands and walk home together.